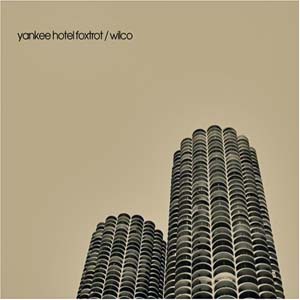

Early in college, I fell in love with Wilco. I know how that sentence sounds, but I’l write it anyway, simply because I also know how many others could write the same thing. Or if not about Wilco, then about some other band that has become synonymous with the glories and terrors of coming of age in a city not your own. So last week’s tenth anniversary of their greatest album, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, was something of a moment for me. Not because I can’t believe it’s been ten years, but mostly because I still haven’t outgrown YHF. So much of what I listened to and read and thought and believed ten years ago has proved both embarrassing and ephemeral. But not YHF. It’s importance has only grown for me. For one, the album has such a stranglehold on my sense of taste, that I can’t help but judge other music’s greatness by its standard. It is truly canonical for me, by which I mean it is a measuring stick for other artists and albums. For another, it in some sense shaped my own sense of wanting to write. More on that later.

Before YHF came out I had devoured *Being There* whose tracks “Misunderstood” and “Sunken Treasure” stand among my favorite all time songs. And Summerteethwas a revelation–Beatles and Beach Boys filtered through alt-country swagger. Still, for all their greatness and the obvious experimentation in those albums, nothing could have prepared me for YHF.

I bought the album the day it came out, back when people did such things. On the way home, I sat alone in my car and listened to the opening track over and over. The seven minute dream wrapped in a nightmare wrapped in a dream that is “I am trying to break your heart” took immediate hold of me. I don’t even remember driving back to my dorm. I only remember listening to that song on repeat and the vague impression of lights flashing and passing me in the dark. It was the strange lyrics, the almost haphazard drums, the plink of the child’s piano, the strained and weary voice. But mostly it was the swirl of noise, the impending sense of chaos. I reveled in the noise, turned up the volume, let it wash over me.

As the best articles celebrating the tenth anniversary of the album have pointed out, the whole album is about wanting to be understood and also about the terror of actually being understood. It’s about vital messages coded in noise and misdirection, and about the hope and fear there is someone on the other side to both receive and decode those messages. Those messages come mostly in the form of ambiguous lyrics. I will never really know what “I am an American aquarium drinker” means exactly. I can’t exegete the deeper meanings of “take off your bandaids cause I don’t believe in touchdowns,” or delve the implications of “our love is all of God’s money.” But I love these lines. Such lyrics are at once ambiguous and earnest. They are exactly the things I was trying to say, but couldn’t or wouldn’t. I understand that these are the very reasons some people hate this album. And in the hands of lesser artists such lyrics are nothing more than nonsense, or worse still unbridled pretension. But for Wilco, layered in the haze of static and delivered in Jeff Tweedy’s broken voice, such lyrics are messages about the inherent fragility of messages. There is so much say and so many ways for that to be misunderstood.

In college I started writing poetry. Partly because I had always wanted to write poetry and partly because I was hopelessly enamored with the girl who edited the literary journal for the English department. The fact that she would read the entries spurred an incredible flurry of terrible poems. And the fact that she would read the entries meant I would never dream of submitting them. Even though they weren’t anything resembling a love poem, and even though they weren’t veiled confessions of devotion, I still felt I would be exposing a nerve. I couldn’t risk being understood.

Eventually, I let other people read versions of those terrible poems. And I even wrote some more. I guess I figured that even if people got it wrong, or worse still got it right, and I was found wanting, it was still worth writing. This may have been because I came to see that the world often feels like YHF sounds.

At the end of “Poor Places,” there is a swell of static, and as it peaks you hear the faint accented voice of woman emerge from the noise. She repeats the phrase, “Yankee. Hotel. Foxtrot,” over and over, even as the static get louder and louder. It is clearly a code, a message veiled in subterfuge. It is not meant to be understood by just anybody. But it is meant to be understood by somebody. I heard those three words, sent out across radio waves, hoping to alight somewhere and to be heard by someone, as an apology for art, as a kind of artifice themselves, a cry made in hopes of making sense of things in the midst of chaos.

In this same vein, I’ve always find a particular lyric in the closing song arresting. In “Reservations” Tweedy sings, “The truth proves it’s beautiful to lie.” Like the rest of the album the statement is veiled in ambiguity, but one way to take it is that the truth makes art necessary. We have to interpret our world, and that world is often enveloped in noise and static, not unlike much of YHF. Even so, we can take the noise and make it into something. When it comes to art, the artifice is a kind of lying, but to me such artifice proves that the world is worth paying attention to and worth interpreting after all. This is certainly why I type out words that maybe only a handful of people will ever read. I am simply trying to make sense of the noise. I am hoping, praying even, that as I tap out dispatches, there is someone on the other end.

Originally Posted by Christopher Myers, May 7, 2012: Earnest Words in Swirling Noise...

Christopher Myers and his wife Morgan live in Dallas, where he attends Redeemer Seminary. In his writing he seeks to examine the beautiful and inevitable overlap of Christianity and culture.

To read more from Christopher Myers, click here.